From https://jerryjenkins.com/story-structures/:

What Is Story Structure?

Structure is to a story what the skeleton is to the human body.

The structure you choose for your story should help you align and sequence:

- The Conflict

- The Climax

- And the Resolution

The order in which you tell your story determines how effectively you create drama, intrigue, and tension, all designed to grab readers from the start and keep them to the end.

Story Structure Elements

You’ll find varying labels for various fiction elements, but really they’re largely similar. All stories include some version of:

1. An Opener

Start with who your story is about and establish the problem, challenge, quest, journey, or dilemma he* faces — and it must carry stakes dire enough to justify an entire book about it. Your goal here is to get your reader invested in the main character and what he must accomplish.

*I use the masculine pronoun inclusively to mean male or female characters.

2. An Inciting Incident that Changes Everything

It’s one thing to render a character frustrated by the status quo or angry at some annoying opponent. But get to the catalyst that forces him to act. The consequences for failing must be dire — way more than frustration or embarrassment. Think of the worst possible result and have your lead character spend the rest of the story battling to prevent it.

3. A Series of Crises that Build Tension

These should be logical—not the result of chance or coincidence—and they should grow progressively worse. In the process of trying to fix things, your protagonist will be building new muscles and gaining skills that will serve him in the end.

4. A Climax

Don’t mistake the Climax for the End. This is where your character appears to have fatally failed and everything appears hopeless.

5. An End

The resolution concludes your story. Your main character must succeed or fail, based on what he’s learned from the crises throughout. This is also where you tie up loose ends and satisfy your reader, while at the same time leaving him wanting more.

7 Story Structures

Need help writing your novel? Click here to download my ultimate 12-step guide.

1. Dean Koontz’s Classic Story Structure

This is the structure that changed the path of my career as a writer.

It catapulted me from a mid-list genre novelist to a 21-Time New York Times bestselling author.

I’m a Pantser, not an Outliner, but even I need some basic structure to know where I’m going, I love that Koontz’s structure is so simple. It consists only of these four steps:

1. Plunge your main character into terrible trouble as soon as possible. Naturally that trouble depends on your genre, but in short, it’s the worst possible dilemma you can think of for your main character. For a thriller, it might be a life or death situation. In a romance novel, it could mean a young woman must decide between two equally qualified suitors—and then her choice is revealed a disaster.

And again, this trouble must bear stakes dire high enough to carry the entire novel.

One caveat: whatever the dilemma, it will mean little to readers if they don’t first find reasons to care about your character.

2. Everything your character does to get out of the terrible trouble makes things only worse. Avoid the temptation to make life easy for your protagonist. Every complication must proceed logically from the one before it, and things must grow progressively worse until….

3. The situation appears hopeless. Novelist Angela Hunt refers to this as The Bleakest Moment. Even you should wonder how you’re ever going to write your character out of this.

Your predicament is so hopeless that your lead must use every new muscle and technique gained from facing a book full of obstacles to become heroic and prove that things only appeared beyond repair.

4. Finally, your hero succeeds (or fails*) against all odds. Reward readers with the payoff they expected by keeping your hero on stage, taking action.

*Occasionally sad endings resonate with readers.

2. In Medias Res

This is Latin for “in the midst of things,” in other words, start with something happening. It doesn’t have to be slam-bang action, unless that fits your genre. The important thing is that the reader gets the sense he’s in the middle of something.

That means not wasting two or three pages on backstory or setting or description. These can all be layered in as the story progresses. Beginning a novel In Medias Res means cutting the fluff and jumping straight into the story.

Toni Morrison’s 1997 novel Paradise begins “They shoot the white girl first.”—the epitome of starting in medias res.

What makes In Medias Res work?

It’s all in the hook.

In Medias Res should invest your reader in your story from the get-go, virtually forcing him to keep reading.

The rest of the In Media Res structure consists of:

- Rising Action

- Explanation (backstory)

- Climax

- Falling Action

- Resolution

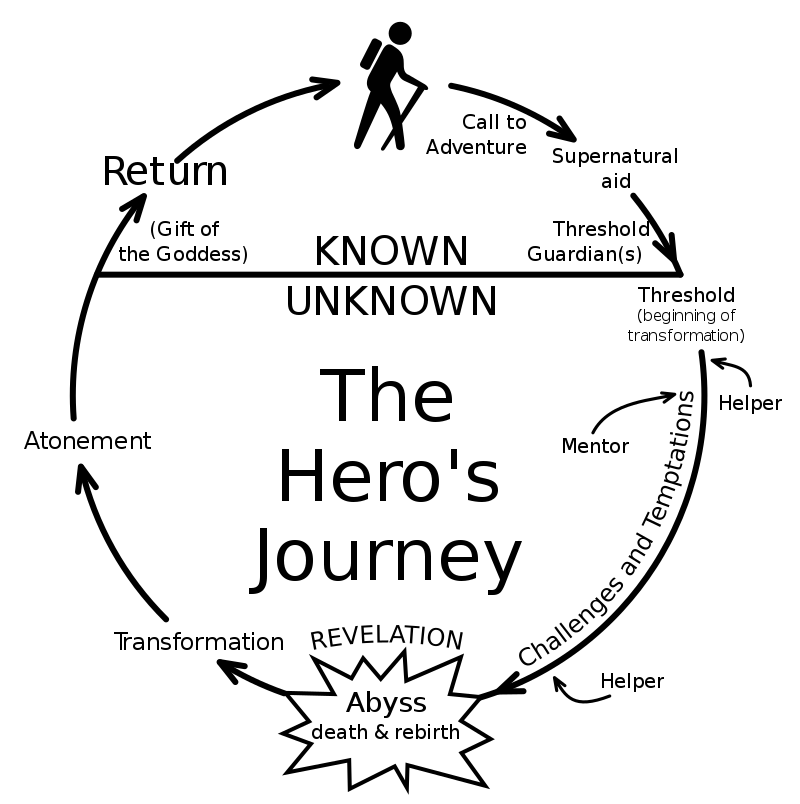

3. The Hero’s Journey

Made famous by educator and widely published author Joseph Campbell, it’s often used to structure fantasy, science fiction, and horror novels.

J.R.R. Tolkien used The Hero’s Journey structure for The Hobbit.

- Step 1: Bilbo Baggins leaves his ordinary world

Baggins is happy with his life in the Shire and initially refuses a call to adventure, preferring to stay home.

The wizard Gandalf (soon to be his mentor) pushes him to accept the call.

Baggins leaves the comfort of his Hobbit life and embarks on a perilous quest across Middle Earth, getting into all kinds of trouble along the way.

- Step 2: Baggins experiences various trials and challenges

Bilbo builds a team, pairing with dwarves and elves to defeat enemies like dragons and orcs.

Along the way he faces a series of tests that push his courage and abilities beyond what he thought possible.

Eventually, against all odds, Bilbo reaches the inmost cave, the lair of the fearsome dragon, Smaug where the ultimate goal of his quest is located. Bilbo needs to steal the dwarves’ treasure back from Smaug.

Bilbo soon finds he needs to push past his greatest fear to survive.

- Step 3: Bilbo tries to returns to his life in The Shire

Smaug may have been defeated, but the dwarves face another battle against others and an orc army.

Near the end of the novel, Bilbo is hit on the head during the final battle and presumed dead.

But he lives and gets to return to the Shire, no longer the same Hobbit who hated adventure.

4. The 7-Point Story Structure

Advocates of this approach advise starting with your resolution and working backwards.

This ensures a dramatic character arc for your hero.

J.K. Rowling used the 7-Point Structure for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

The Seven Points

- Hook: your protagonist’s starting point

In Philosopher’s Stone, this is when we meet Harry living under the stairs.

- Plot turn 1: introduces the conflict that moves the story to its midpoint.

Harry finds out he is a wizard.

- Pinch point 1: applies pressure to your protagonist in the process of achieving his goal, usually facing an antagonist.

When the trolls attacks, Harry and his friends realize they are the only ones who can save the day.

- Midpoint: your character responds to conflict with action.

Harry and his friends learn of the Philosopher’s Stone and determine to find it before Voldemort does.

- Pinch point 2: More pressure makes it harder for your character to achieve his goal.

Harry has to face the villain alone after losing Ron and Hermione during their quest to find the stone.

- Plot turn 2: Moves the story from the midpoint to the resolution. Your protagonist has everything he needs to achieve the goal.

When the mirror reveals Harry Potter’s intentions are pure, he is given the Philosopher’s Stone.

- Resolution: The climax. Everything in your story leads to this moment, a direct contrast to how your character began his journey.

Harry defeats Voldemort.

5. Randy Ingermanson’s Snowflake Method

If you like outlining your story, you’ll love The Snowflake Method.

But if you’re a Panster like me (someone who prefers to write by process of discovery), a story structure like Dean Koontz’s Classic Story Structure or In Medias Res might feel more natural.

The 10-step Snowflake Method

Start with one central idea and systematically add more ideas to create your plot.

- Write a one-sentence summary of your novel (1 hour)

- Expand this into a full paragraph summary, detailing major events (1 hour)

- Write a one-page summary for each character (1 hour each)

- Expand each sentence in #2 into a paragraph summary (several hours)

- Write a one-page account of the story from the perspective of each major character (1-2 days)

- Expand each paragraph you wrote for #4 into a full-page synopsis (1 week)

- Expand your character descriptions into full character charts (1 week)

- Using the summary from #6, list every scene you’ll need to finish the novel

- Write a multi-paragraph description for each scene

- Write your first draft

6. The Three-Act Structure

This formula was used by ancient Greeks, and it’s one of Hollywood’s favorite ways to tell a story.

It’s about as simple as you can get.

Act I: The Set-Up

Introduce your main characters and establish the setting.

Brandon Sanderson, a popular fantasy writer, calls this the “inciting incident”— a problem that yanks the protagonist out of his comfort zone and establishes the direction of the story.

Act II: The Confrontation

Create a problem that appears small on the surface but becomes more complex. The more your protagonist tries to get what he wants, the more impossible it seems to solve the problem.

Act III: The Resolution

A good ending has:

- High stakes: your reader must feel that one more mistake will result in disaster for the protagonist.

- Challenges and growth: By the end, the protagonist needs to have grown as a person by overcoming myriad obstacles.

- A solution: All the trials and lessons your character has endured help him solve the problem.

Suzanne Collins’s bestselling young adult trilogy, The Hunger Games, uses the three-act structure.

7. James Scott Bell’s A Disturbance and Two Doorways

In his popular book Plot and Structure, Bell introduces this concept.

- A Disturbance early in the story upsets the status quo—anything that threatens the protagonist’s ordinary life.

- Doorway 1 propels your character to the middle of the story. Once he goes through this door, there’s no turning back.

- Doorway 2 leads to the final battle. It’s another door of no return but usually leads to disaster.

The Umbrella Academy by Gerard Way uses this story structure.

Upon hearing that their adoptive father has passed away (the disturbance), six siblings return to their childhood home.

Here they learn the world will end in a few days (Doorway 1). While the siblings try everything in their power to stop the potential global apocalypse, they unwittingly create another threat amongst themselves.

This leads to a final battle (Doorway 2).

From https://jerichowriters.com/hub/plot/:

Outline your Novel Fast, Easily and Well with this Simple Story Template

All stories share a simple common structure, right? So the simplest way to outline your novel (or any type of story) is to use that universal template by way of scaffolding.

And you do need to use some kind of novel outline before you start writing. Plotting a novel from scratch? Imagining the whole thing in your head before you start? That’s hard.

Or, scratch that, it’s pretty much impossible.

So don’t do it. Cheat. Use a simple, dependable template to build an outline of your novel, then slowly fill out the detail.

Yes, filling in the detail can be a slow and tricky process. But you don’t care. Because if your basic outline is strong (and the idea that lies behind it is strong), you can’t really go wrong.

And figuring out that template and how best to use it is exactly what we’re going to do in this post. (Or – full disclosure – it’s what you’re going to do. We’ll just help a little on the way . . .)

Novel outline template in a nutshell

You just need to figure out:

- Main character (who leads the story)

- Status Quo (situation at the start)

- Motivation (what your character wants)

- Initiating incident (what disturbs the status quo)

- Developments (what happens next)

- Crisis (how things come to a head)

- Resolution (how things resolve)

What a story template looks like

Use a simple plot outline to get your ideas straight

Let’s start simple.

And that means, yep, that YOU need to start simple. Get a sheet of paper or notebook and have it by you as you work your way through this post.

Ready? Pencil sharp and ready to go?

So do this: Write down the following headings:

Main characters

Status Quo

Motivation

Initiating Incident

Developments

Crisis

Resolution

Simple right?

And now sketch in your answers in as few words as possible. That means a maximum of 1-2 sentence for each heading there. If that seems a little harsh, then I’ll allow you 3 sentences for the “Developments” section: that’s where the bulk of your book is going to lie.

But that’s all. At this stage, we don’t want complex. Complex is our enemy.

We’ll get there soon enough, but for now just think, Structure-structure-structure. Too much complexity – all that intricate plot detail – just gets in the way of finding the actual bones of your novel.

(Oh, and I don’t want to digress too much, but that same basic template works if you want to build a scene, or write a synopsis, or structure a key piece of dialogue. In fact, it’s just like this universal unlocking device for pretty much any structural challenge in fiction. Good to know, huh?)

The novel template: an example

You probably want an example of what your outline should look like, right? OK. So let’s say your name was Jane Austen and you had a great idea for a story about a prideful guy and a charming but somewhat prejudiced girl. Your story outline might look something like this:

Character

Elizabeth (Lizzy) Bennet, one of five daughters in Regency England.

Status QuoLizzy and her sisters will be plunged into poverty if her father dies, so they need to marry (and marry well)

Motivation

Lizzy wants to marry for love.

Initiating IncidentTwo wealthy gentlemen, Mr Bingley and Mr Darcy, arrive.

DevelopmentsLizzy meets proud Mr Darcy and dashing stranger Mr Wickham. She despises Mr Darcy and likes Mr Wickham. She discovers Darcy loves her and that Wickham isn’t all he seems.

CrisisLizzy’s sister elopes, threatening the social ruin of her family. It now looks like Lizzy can’t marry anyone.

Resolution

Mr Darcy helps Lizzy’s sister. Lizzy agrees to marry him, deciding now that she loves him, after all.

Now that’s easy, right? That’s the whole of Pride and Prejudice in a nutshell, and it was easy.

You just need to do the same with your book or your idea, and keep it really simple. In fact, if you struggle to know everything that goes in the ‘developments’ section, you can even drop in some placeholder type comments. If you were Jane Austen you might, for example, start out by saying something like “Lizzy breaks with Wickham, because it turns out he’s a bad guy. He killed someone? Stole money? Something else? Something to think about.”

And that’s fine. Don’t worry about any blanks. It’s like you’re building a tower and you’re missing one of the girders. But by getting everything else in place and putting a “girder needs to go here” sign up, the structure is still brilliantly clear. That’s all you need (for now.)

Oh, and don’t bother separating those down into chapters just yet, you can worry about that later – but when you do, read this, it’s really useful!

Finally, don’t complicate things if you don’t want to, but if you find it helpful to add a “character development” heading, then you should do that as well. Effectively, you’re extending your novel outline template to cover not just plot movements, but character development too – a brilliant all-in-one tool.

Developing Your Story Outline

Taking your template on to the next level

Now, OK, you might feel that our template so far is just a little too basic.

Which it is.

So let’s develop the structure another notch, and what we’re going to do now is to add in anything we know about subplots – or basically any story action that you DO know about, which doesn’t fit neatly into the above plot structure.

So if you were Jane Austen, and had a good handle on your story, you might put together something like this. (Oh, and we’ve called them sub-plots, but you can call them story strands, or story elements, or anything that feels right to you.)

Subplot 1

Jane Bennet (Lizzy’s caring sister) and Mr Bingley fall in love, but Bingley moves away, then comes back. Jane and Bingley marry.

Subplot 2

Lydia Bennet (Lizzy’s reckless sister) elopes with Wickham. She is later found and helped by Darcy.

Subplot 3

Odious Mr Collins proposes marriage to Lizzy. She says no. Her more pragmatic friend, Charlotte Lucas, says yes.

Notice that we’re not yet trying to mesh those things together. In fact, the way we’ve done it here Subplot 3 (which happens in the middle of the book) comes after Subplot 2 (which comes at the end).

But again: don’t worry.

Sketch your additional story material down as swiftly as neatly as Miss Austen has just done it. The meshing together – the whole business of getting things in the right order, getting the character motivations perfectly aligned and all that – that’ll do your brain in.

Yes, you have to get to it at some stage. But not now. Keep it simple, and build up.

And that actually brings us to another point.

How to use subplots

If you’re a fan of Pride and Prejudice, you’ll know perfectly well that our outline so far still misses out masses of stuff.

There’s nothing on where the novel is set. Or why or how events unfurl. It doesn’t say a thing about character relations, why each feels as they do. There’s nothing to say on character development, subtleties, supporting cast, and so on.

And that’s fine to start with. It’s actually good.

What does matter, however is your character’s motivation.

Taking one subplot above as example, Charlotte wants security through marriage to Mr Collins. Lizzy, however, rejects her friend’s rationale. Charlotte’s marriage reaffirms Lizzy’s romantic values and, crucially, also throws her in Mr Darcy’s way again later in the book.

Now that’s interesting stuff, but if a subplot doesn’t bear on a protagonist’s ability to achieve their goal or goals, that subplot must be deleted or revised. Luckily, though, our story structure template helps you avoid that pitfall in the first place.

In fact, here are two rules that you should obey religiously:

- If you’re outlining a plot for the first time. Pin down your basics, then build up subplots and so on.

- If you have already started your manuscript and you think you’re uncertain of your plot structure, stop – and follow the exercises in this post, exactly as you would if you hadn’t yet written a word.

And do actually do this. As in pen-and-paper do it, not just “think about it for a minute or two then go on Twitter.” The act of writing things out will be helpful just in itself.

The act of writing always is.

Plotting your novel: the template

Remember as well that every subplot (or story strand, or whatever you want to call them) has its own little journey. Maybe a very simple one, but it’ll have its own beginning, middle and end. Its own structure of Initiating Incident / Developments / Crisis / Resolution.

So you may as well drop everything you have into the grid below.

(If you want to adapt that grid a little, then do, but don’t mess around with it toooo much. The basic idea there is golden.)

| Main plot | Subplot 1 | Subplot 2 | Subplot 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiating incident | ||||

| Main plot | ||||

| Crisis | ||||

| Resolution |

If you’ve got more complexity to accommodate than this allows, take care. No matter how sprawling an epic you’re writing, you need to be able to identify the essence or heart of the story you’re writing, so try paring your novel down – you can always add more details and columns after.

What would your story look like, if you did this?

How to further develop your plot outline

Advanced techniques for writing ninjas

What happens if your plot doesn’t fit into that grid? If you give that exercise your very best go and just draw a blank?

Well, no worries. The basic problems here are twofold:

- You don’t yet understand your plot well enough, or

- You just don’t have enough plot to sustain a full-length novel.

Two different problems. Two different solutions.

If you don’t yet understand your own plot in enough detail, you want to use …

Plot-Building Tool: The Snowflake Method

Seeing your own plot in detail, before you write the book, is really hard, because it’s like you’re standing on the seashore trying to jump onto Mount Everest. In one bound.

Not gonna work.

So get there in stages, Base Camp. Camp 1, and so on up.

What that means for you, is that you use our basic template in sketch form to start with – a sentence or two per section. Then you go at it again, and give each section its own paragraph. Then you go at it again, expanding to 2-3 paragraphs, or whole pages if you want to.

The same basic exercise, but getting into deeper levels of detail each time.

If you want more about the “snowflake” approach you can find it right here.

OK.

But what if your plot outline just feels a little bit thin once you sketch it out?

Answer you fix it – and you fix it NOW before you start hurtling into the task of actually writing.

Here are the techniques you’ll need to do just that:

Method 1: Mirroring

This doesn’t mean tack on needless bits and pieces – characters shouting at each other for effect, etc. – but add depth and subplots, developing the complexity of your protagonist’s story. (Remember: if it’s not contributing to your protagonist’s journey, it doesn’t matter and you need to delete it.)

To take another novel – supposing your name is Harper Lee, and your story is the tale of a girl named Scout – let’s say Scout’s spooked by an odd but harmless man living on her street. It’s fine, though there’s not yet enough complexity yet to carry a novel, so complicate it.

One thought is giving her a father figure, say a lawyer, named Atticus. (Harper Lee herself was daughter of a small-town lawyer.) He’s fighting to defend a man accused of something he obviously didn’t do. Targeted for who he is, rather than anything he’s done.

A black guy accused for looking different? An odd-but-harmless guy who spooks Scout?

It’s straightforward, tragic mirroring. Atticus’ fight is lost, the stories interweave, and Scout learns compassion in To Kill A Mockingbird.

Introducing that second, reverberating plot strand meant that Harper Lee’s novel had the heft to become a classic of world literature.

Method 2: Ram your genre into something different

Another way to complicate your plot is to throw action into a different genre – such as sci-fi, fantasy or crime.

So take The Time Traveler’s Wife, by Audrey Niffenegger.

Looked at one way, that’s a pretty much standard issue romantic story, which, yes, could have sold, but could never have made the huge sales it actually racked up. But then ram that into a story of time-travel, and you have something shimmeringly new and exciting.

What you had was still a romantic story at its heart – it certainly wouldn’t appeal to hardcore fans of SF/fantasy – but the novel element gave it a totally new birth.

Or take Tipping the Velvet, by Sarah Waters.

A picaresque Victorian historical novel . . . that kind of thing always had its audience – but that audience had never encountered a frankly told lesbian coming-of-age story in that context, and the result of that shock collision was to produce a literary sensation.

Method 3: Take your character and max her out

Why was it that The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo went on to get such gigantic sales across the globe?

It wasn’t the quality of Stieg Larsson’s writing, which was never more than competent and which was quite baggy, to say the least. And the actual plot? Well, on the face of it, he delivered a fairly standard issue crime story. Nothing so unusual there in terms of actual narrative.

But Stieg Larsson rammed that basic story with an exotic character: Lisbeth Salander. That woman had Aspergers, she was a bisexual computer hacker and rape survivor . . .and boom – vast worldwide sales resulted.

Method 4: Add edge – a glint of steel

A few years back, I was struggling with one of my books, This Thing of Darkness. (here)

The basic plot was strong. The mystery element was good. There was at least one quite unusual element. The climax was rip-roaring (set on a trawler at sea in a force 10 gale.) But . . .

The book wasn’t quite working.

It was long. And it was just a long, long way from the set-up phase of the book to the denouement.

My solution?

A glint of steel.

I took an incident from the middle of the book – a break-in, and a theft, but no violence, no real time action – and I turned that into a long sequence involving the abduction of my protagonist.

That addition made a long book even longer . . . but it made the book.

It’s not just that the sequence itself was exciting, it’s that its shadow extended over everything else too. Whereas before the book had felt a bit like, “yep, gotta solve the mystery, because that’s what these books have to do.”

Now it was: “We HAVE TO solve that mystery, because these bastards abducted our protagonist.”

Steel. Edge. Sex or violence.

Those things work in crime novels , but they work in totally literary works too. Can you imagine Ian McEwan’s Atonement without that glint of sex? Would The Great Gatsby have worked if no one had died?

How to write a plot from multiple perspectives

If you’re eager to write about multiple protagonists, you need a plot outline, along the lines of the template above, for each one.

George R.R. Martin took this to new levels in A Song of Ice and Fire, each protagonist having his or her own richly developed plot and character arc.

John Fowles’ The Collector, for example, is narrated by a kidnapper and the girl he’s kidnapped. Sullen, menacing Fred justifies all he does. Miranda chronicles her fear and pity. The result is taut, terrifying. We’re engrossed in their shared experience to the end.

Multiple protagonists can work in romance novels, too, even ones told in third-person narration, such as The Versions of Us by Laura Barnett, or Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell.

This said, managing multiple points of view, even from minor characters, can work well for thrillers, often driven by the drip-drip-drip of information release (though these things depend on story, as much as genre).

The key thing to bear in mind here is that you need a mini version of your novel outline template for each of your main characters. Each one of those guys needs a complete little story of their own – and those little stories need to interweave to create one great and compelling one.

From https://jerichowriters.com/hub/plot/plot-diagram/:

The Plot Mountain

What it is. How to chart it. How to find the right structure for your novel.

Plot structure is one of the trickiest and most vital things to get right in a story, but using the idea of a plot mountain can be a great way to solve your plot problems – and deliver a great experience for the reader.

Plot is loosely defined as a chain of events in a story – i.e. this happened, so that happened.

Notice that little word “so” – it means that Y happened, because X happened. That everything in your story is linked together, literally like links in a chain.

A linear, logical chain of events, though, isn’t all that exciting. You need a story arc – a plot mountain – to engage readers, to build tension and excitement.

Here’s what you need to know.

Free plotting worksheets

Make the hardest part of writing easierGET YOURS

Use a plot diagram for story momentum

A plot diagram (or plot mountain or story arc) will deliberately look like a triangle, with action and drama building to excite us before subsiding.

It mightn’t sound inspired. To most readers, a story is a living thing and you’re alive in those writers’ very dreamscapes.

Often, though, rules can help keep a writer on track. (And once understood, they can be bent and broken a little.)

Consider a plot mountain your roadmap for sustaining emotional momentum through the story – and let’s cover some points.

Plotting your foundations (your characters)

Any foundation for a good story is character.

It may veer on a cliché, but think of it as inverse pot-of-gold at the start of a rainbow. The more you bury early on, the more you can mine and dig up later over your plot mountain. Character is only the start of good plotting, but it is no less than that. The best stories are essentially character journeys.

Your protagonist will need to be human and compelling. Your protagonist will also be in need for a story arc to take place, so they must lack something. This is your foundation for a good story. Start here and think of both your character’s goal or goals, as well as your character’s motive(s).

This distinction between goal and motive is important.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter needs love and acceptance (motive), having grown up uncared for under his uncle and aunt’s roof. Then Hagrid appears and Harry ‘needs’ to escape to Hogwarts (goal). Harry’s goals change through the books (going to the Quidditch World Cup, winning the Triwizard Tournament). But his motivation is to fight throughout for peace and tolerance – and his overarching goal has evolved by the last book to be the death of Voldemort and peace for the wizarding community.

So map goal to motive as you plan for your character’s growth, their story arc and your plot structure – and take a look at our character building page for help, ditto how authentic characterisation is essential to help drive a plot forward.

Character needs may evolve as your hero or heroine grows, but goals and motive can’t be ‘illogical’ and cancel out the other (e.g. you write in a goal not in keeping with your character’s nature).

And remember any story is born out of your protagonist desiring something, rooted in overcoming weakness to get to a stronger new equilibrium. (We’ll get to this soon.)

Plotting your initiating incident

Having mapped out your foundation and novel beginnings, you can tie in your initiating incident. A good example might be Harry Potter receiving his Hogwarts letter. Out of the Cupboard under the Stairs, onto Hogwarts. And any initiating incident or call-to-action, no matter how over- or understated, must actually throw the character into a worse-off situation than the start in order to set your novel off on the right trajectory.

Story charts are called ‘story mountains’ in schools, after all, because stakes get higher and things need to get emotionally a lot tougher before they can wind down to a happy ending.

So the initiating incident you just kindled should spark drama. It should lead your protagonist into what we’ll (loosely) call a fraught setup where drama will unfold.

It looks as if Jon Snow’s going to the Night Watch will result in a quieter life than the trauma unfolding for his family in King’s Landing. Jon’s choice leads him to danger instead. And it looks as if Harry Potter will be safe at Hogwarts under Dumbledore’s watch. And it looks as if Jane Eyre will be settled and happy at Thornfield.

A good plot subverts such hope. Your drama builds from this.

The protagonist is placed, somehow, in some jeopardy that rivets us and pushes us to read more, so bear in mind your initiating incident carefully.

You’ll later need to subvert our sense of safety as you ‘bridge’ your way to your next plot points and remember your initiating incident should map back to earlier foundations (your character’s nature). Will they take up their call and be right for your plot structure and story arc?

Make sure it marries up to motive, with the person they are at heart. You need a protagonist to actively take this call-to-action up.

This is true even for reluctant heroes, i.e. Arthur Golden’s Chiyo in Memoirs of a Geisha or Suzanne Collins’ Katniss in The Hunger Games. Chiyo tries to run away at first, fails, but she finds other reasons to train as a Kyoto geisha and remain in her okiya. Katniss volunteers for the Hunger Games in her sister Prim’s place, with no choice but to fight to save her sister. Once she’s committed, she’ll fight to survive.

Some protagonists are more proactive and will create their own ‘call’, rather than fairy-godmother-summons. Jon Snow, for instance, opts to leave home and ‘take the black’ in A Game of Thrones. Jane Eyre is at first sent to school, then creates her ‘call’ because, bored years later, she advertises herself as a governess.

Whether your protagonist knows an initiating incident could lead them to danger (as Katniss does), they still can’t help taking up the mantle. They’ll always choose to take up the call, and so it always maps back to intrinsic needs. Katniss needs to save her sister because she couldn’t live with herself if not in The Hunger Games.

And the rest of your plot is about mounting drama and the protagonist reaching their end goal.

Creating plot development

Plot development’s where you get to wreak havoc and brew drama, the clouds and storms gathering up the plot mountain. So play with scenarios and ideas.

Be sure everything is done right when you edit your plot, keeping all that happens to your protagonist relevant and necessary, and don’t meander, but do get your ideas down. Plotting should be fun and, like a first draft, you can edit and hone as you go.

As Edgar Allan Poe wrote, ‘no [plot] part can be displaced without ruin to the whole.’

You also need here to accordingly sketch your antagonist (if not fleshed out yet), and they’ll compete for the same thing as your protagonist.

Yes, really.

According to storyteller John Truby in The Anatomy of Story, a good protagonist and antagonist compete for ‘which version of reality everyone will believe’.

Think of everyone in A Song of Ice and Fire vying for the Iron Throne. This is a story of many people believing they should rule – and George R.R. Martin’s multiple protagonists work as one another’s antagonists. Each has a version of reality they want to assert. And we’ve invested emotionally in all these characters and rivals, which is why A Song of Ice and Fire is so gripping.

Your story arc (or the bulk of it) is in fact about which reality will be established if your protagonist fails and the conflict resulting from this threat is the rising action. This is where your story tension, drama, poignancy and urgency will be born.

And there’s just no point in mismatching protagonist and antagonist, any more than you’d mismatch your love interest in a romance novel, if you want drama ensuing.

Create your character’s very antithesis, then.

Who’d be the worst antagonist for your protagonist to be faced with? Bring them to life. Which gifts would be the ultimate worst-case scenario for your protagonist to deal with? Give them those gifts. Make it personal and keep it human. This isn’t just about plot mechanics, either: a protagonist-antithesis means your character’s journey will end in real growth and change, that stakes will be heightened.

And a face often grips us more than a secret network, machine or monster. There are exceptions, i.e. Frankenstein’s Monster, or White Walkers, but there’s still a ‘humanness’ in really monstrous beings that makes them more sinister. Cersei Lannister is more ominous than Daenerys’ dragons in A Song of Ice and Fire. Cold Aunt Reed and petulant Blanche Ingram aren’t larger-than-life murderesses à la Cersei, but they’re larger-than-life threats to Jane Eyre and Jane’s hopes for happiness.

Bar a gripping (powerful, threatening) antagonist, there aren’t set rules for rising action, but a good story checklist of things to include could be:

- Create your antagonist with care and add psychological ‘meat’ when setting up an opponent or supporting opponents, something for us to discover (their views, value set, etc.), and write in how something about them hinders your protagonist growing, flourishing, getting where they need to be;

- Create ‘surprise reveal’ moments with care in your plot structure, sharing new information for characters, and with the result of ennobling or refining protagonist attitudes and goals;

- Create a protagonist’s goal or plan and your antagonist’s counter-goal or plan, giving equal care to both, no matter your genre (e.g. Katniss Everdeen plans to survive the Hunger Games whilst the Capitol tries to crush her in various ways);

- Create plot setbacks and comebacks, e.g. Jane Eyre’s seemingly found freedom and happiness on her engagement, before being thrust back (by discovering Rochester’s wife);

- Create pieces of foreshadowing for readers to pick up on;

- And create plot events and actions consistent with your protagonist drive, remembering your original character motivation as you weave it through your drama to keep its heart.

You’ll want to throw in allies, true and false, betrayals or misunderstandings, perhaps red herring threats and veiled or surprise threats. And any subplot characters should be dealing with the same issue or issues as your protagonist, or there’s no point to them (at least in your story terms).

If nothing else – be sure you’re building up your character’s desire for their goals. The stakes should be getting tougher. The choices should be getting harder. These things should be building throughout, so the goal becomes more urgent as plot jeopardy mounts in your story arc.

Remember that everything you map here needs to map back to character revelations, to shifting goals. This too maps up to story climax and to your protagonist’s emotional catharsis (when you’re mapping out ‘falling actions’ later).

Pinpointing your character revelations

Character revelations are key to great plotting, as otherwise it all grows rather mechanical – and plotting and characterisation are such infused, melded, twisted-together processes, after all. There isn’t one without the other.

It’s been said we often do the best we can with the information we have. As such, your protagonist needs ‘surprise reveal’ moments where some new information is shared for their character growth and for plot development to happen. So, as mentioned, rising plot tensions should accommodate ennobled motives and, sometimes, slightly altered goals for a compelling story arc.

Again, Harry Potter has several important revelations over his series and these change his goals and the nature of them. Growing up in Hogwarts, Harry gradually grasps his power to make a difference. He starts teaching Hogwarts students defensive magic. Trying to save Sirius, Harry learns even his best efforts ‘playing the hero’ can lead to tragedy. Harry then works with Dumbledore to become less a moving target than an active fighter, as he learns more about Voldemort’s origins, how to anticipate him as Voldemort anticipated Harry’s efforts to save Sirius.

Such revelations should marry up with key plot points (or plot events).

There aren’t set rules, per se, as to when character revelations should appear, how often and which ones. It’ll all depend on story and your characters. But it’s important to punctuate your plot chart with revelatory moments, building in importance for growing urgency.

Revelations are a story’s heartbeat, meat and blood.

Plotting your story climax or crisis

Plot events can be climactic, but there’ll typically be one major climax or crisis. (There are exceptions.) Choose it, build to it, plot it carefully.

It’s Clarice Starling’s showdown with Buffalo Bill, Jane Eyre’s ghostly summons across the moors back to blinded Rochester. In the simplest terms, Robert McKee defines any story climax, in Story, as ‘absolute and irreversible change’. And in John Bell’s Plot and Structure, story crises are transition points called ‘doorways of no return.’

So a story climax is (structurally) also something that’ll set up for a resolution, for falling action and a new order of things. Bear this in mind, especially if you’re feeling confident enough to create multiple major crises (more of a plot mountain range). And whilst your protagonist may have gone through many other big challenges and changes, this should be irreversible, and there should be some self-revelation tied up here.

Clarice Starling’s self-revelation is one of self-belief. She’s not ready to take on Buffalo Bill, but she does. She beats him. And she learns she could beat him. This question of her aptitude hung on Clarice’s many conversations with Hannibal. The story’s been leading us to this point.

A crisis (as above) is the peak of your story arc, and pinnacle of a protagonist’s self-revelation. And the rest is about winding down, dealing with the emotional aftermath.

Plotting your resolution or new equilibrium

Your protagonist’s world is, very simply, either better or worse now the story climax is over. From this, you’ll plot your resolution as your story arc falls.

Your protagonist has either achieved their goals after their battles and evolution and self-discovery – or not – and so there also needs an emotional catharsis. Your story mustn’t lose heart simply because we’re winding down. Your falling action plays a vital cathartic role for both your characters and your readers.

Clarice Starling, for instance, defeats Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs, becomes an FBI agent. She has saved her first victim in Catherine Martin, or ‘lamb’, after the lambs’ cries that have haunted her sleep before now (because Clarice couldn’t help or save them).

Think again of Robert McKee’s ‘absolute and irreversible change’, John Bell’s ‘doorways of no return’. Clarice’s door, if you will, has opened onto a new life and Clarice can’t go back to the lesser life experience she had.

This is the new equilibrium. You’ll create the same for your characters as you wind down. In this instance, Clarice is an agent, and Buffalo Bill is gone. But Hannibal is at large. There is still danger in paradise, and scope for Thomas Harris’ sequel, Hannibal.

In A Game of Thrones, the climax is Eddard Stark’s beheading. And with the demise also of King Robert, the new equilibrium is set for dystopia under King Joffrey Baratheon, with Sansa Stark his hostage, and Arya Stark on the run, as Robb Stark rallies in the north. A Game of Thrones sets the stage for its sequel, A Clash of Kings.

In romantic Jane Eyre, Jane is happily united with Rochester. The new equilibrium is a happy ending, but after the novel’s crisis (her refusal to marry Rivers, hearing Rochester calling on the moors), the build-up to Jane’s new equilibrium, her happy reunion with Rochester, is cathartic because it is written as such. The same is true in Memoirs of a Geisha. Chiyo (now called Sayuri) writes readers a dreamy fairy tale end after her final talk with the Chairman, her emigration to America.

So, when you’re ending your tale, think of the new equilibrium you’re establishing and don’t deprive readers of a cathartic end just because you’re in a hurry now to finish plotting.