5 Great Writers Who Stole The Idea You Know Them For

Coming up with a great idea is one of the hardest parts of the creative process. Of course, the process is infinitely easier if you don’t mind “borrowing” (a phrase here meaning “straight-up lifting”) a few ideas from other people.

As it turns out, tons of famous writers have circumvented the whole creative process thing by propping the literary Hondas of other authors up on cinder blocks and stripping them of all their best parts. There’s a fair chance that some of your favorite books are shameless rip-offs of other, less fortunate authors who made the critical mistake of never becoming famous.

5 William Shakespeare Straight-Up Stole Othello and Romeo and Juliet

Cracked loves William Shakespeare, and for good reason. The man’s an innovator of the English language, a dirty jokester, and a man who enjoys feeding minor characters to bears. He also popularized the Michael Bolton haircut centuries before it was ruined by Michael Bolton.

And he rocked the hoop earring before Michael Jordan made it legit.

The Work He “Borrowed” From:

Let’s start with Othello, which stands among the pinnacle works of Shakespeare’s remarkable career. Chronicling the misadventures of a noble but fantastically naive Moorish captain of Venice, the play is a legendary tragedy of racism, distrust, jealousy, and betrayal. And, as if he were trying to live his life according to the themes of his famous play, Shakespeare stole the ever-loving shit out of it.

A little-known Italian novelist and poet named Giovanni Battista Giraldi, also known as Cinthio, wrote a short story in 1565 titled Un Capitano Moro, which historians have noticed shares certain elements with Shakespeare’s Othello. Which elements, you ask? Oh, nothing major; just the plot, characters, certain names, setting, and moral. Cinthio’s version of the story is so similar to Shakespeare’s acclaimed play that we’re surprised Shakespeare even bothered to change the title before ripping it right the fuck off.

“Eh, nobody’s going to remember this Cinthio guy.” — William Shakespeare

This isn’t exactly an isolated case of Shakespeare behaving like a college freshman struggling to piece together a last-minute term paper by hitting Ctrl V of entire sections of Wikipedia; Romeo and Juliet was noticeably “inspired” by a 1562 narrative poem called The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet. While The Bard generally stuck to ancient historical or oral legends when researching his plays, Othello and Romeo and Juliet stand out for being fairly contemporary works that he adapted without citation. There’s also the fact that they’re two of his most successful tragedies, but that’s surely just a coincidence.

The reason history doesn’t know Shakespeare as the first serial plagiarist is that he wasn’t technically doing anything wrong. Shakespeare started popping out his plays during the final decade of the 16th century, which predated the Statute of Anne in 1710 by over 100 years. The Statute of Anne was the first piece of legislation that granted intellectual property rights and protection to owners of creative works, which means that Shakespeare was pulling all his tragedy-stealing bullshit before the act was truly illegal. However, he still knew enough about stealing other people’s work to not credit the original authors of Othello and Romeo and Juliet in any way. So, while Shakespeare wasn’t technically guilty of plagiarism, he was still guilty of being an asshole.

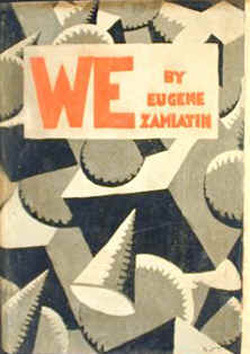

4 George Orwell Lifted the Plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four From an Obscure Russian Novel

Nineteen Eighty-Four is the famous dystopian novel by George Orwell that didn’t feature talking pigs. A powerful and terrifying story of a totalitarian society watched over by the omnipresent Big Brother, its themes have influenced everything from TV shows to video games to irritating roommates who have never actually read the book but know to use the phrase “Big Brother” when referring to the Social Security deduction on their GameStop paycheck.

“No parking for lunch on Tuesday? This is literally what Orwell was warning us about.”

It is arguably one of the most original pieces of fiction ever written, and has had no shortage of shameless imitators try to duplicate its thought-provoking themes over the years.

Yeah, about that …

The Work He “Borrowed” From:

The central theme and many important plot points came from a little-known Russian author named Yevgeny Zamyatin. You could write it off as coincidence, but in 1946 (three years before Nineteen Eighty-Four was published) Orwell reviewed Zamyatin’s novel We and raved about Zamyatin’s grasp of contemporary politics and that of the dehumanized individual in modern society. Then he went on to use the shit out of said themes in his own book.

“The best books, he perceived, are those that tell you what you know already.”

Still, it would be no big deal if it was just that We and Nineteen Eighty-Four were both scathing critiques of totalitarianism and collectivization — that’s a whole genre. But Orwell decided to go further with his “borrowing” of Zamyatin’s work. We has a variation of “thoughtcrime” called “imagination”, and a “Big Brother” called “The Benefactor.” Both novels see the ruling class inflict a form of elaborate torture on potentially dangerous thinkers to “adjust” their temperaments. Both novels use a mathematical equation motif (2+2=5 in Nineteen Eighty-Four, the square root of -1 in We) to represent the incompatible logic of the protagonist and the fictional police-state. Both feature a downbeat ending that sees the protagonist declare his love for the evil administration.

The two books aren’t 100 percent identical, but the important elements are all there. In Orwell’s defense, his book is undeniably better, like Star Wars compared to all the movies George Lucas ripped off to put it together. What’s more, it never really occurred to Orwell that his novel could ever change the literary world to the extent it did or, for that matter, at all. His correspondence hints that he treated Nineteen Eighty-Four as merely “a little squib” he happened to be writing, fully knowing and accepting that it was blatantly “not O.K. politically” and might never see the light of day at all. Basically, he was just writing some We fan fiction that somehow got turned into a huge industry. Sort of like 50 Shades of Grey.

3 Benjamin Franklin “Borrowed” Quips from a British Satirist

Ben Franklin, the glorious Doctor Frankenstein to the monster that is America, had enough wit to fill three heads, and wasn’t too shy about showing it off. One of his many creative outlets was writing under his pen name, Richard Saunders, under which he could — and often would — behave like a goddamn troll if he felt like it. The Saunders persona was in charge of Poor Richard’s Almanack, the advice and diss-track filled serialized almanac that was first published in the early 1730s. Its many quips and common sense advice are often credited for inventing American literary culture, and the publication did wonders for Franklin’s wallet and writing career.

His liver? Not so much.

But how could one man — even a nation-founding, lightning-taming, skullet-sporting beast of legend — take time from his hectic schedule of constructing history to constantly come up with such fine material?

Well the answer is, he couldn’t.

The Work He “Borrowed” From:

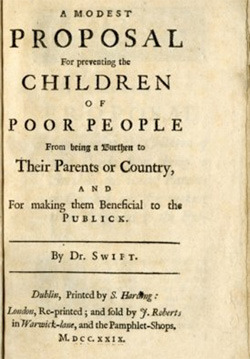

Ben Franklin was a complete genius, no doubt about it. Nonetheless, when it came to collecting material for his Almanack, he was prone to borrowing from his peers. In fact, most of the best quips from Poor Richard’s were either stolen verbatim from a number of classical writers or were slightly reworked proverbs. A particular target of Franklin’s was the famous British satirist Jonathan Swift (the guy responsible for Gulliver’s Travels and suggesting that we all eat Irish babies to fight famine). Not only did Franklin liberally pilfer Swift’s material, but it’s entirely likely that the idea of writing a humorous almanac was Swift’s in the first place.

So, basically, the genius of the colonies was stealing from a dead baby comic like a common seventh grader.

Starting in 1708, Swift began printing a series of pamphlets of his own, with notable similarities to Franklin’s later endeavor. Swift, using the Britishly hilarious pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff, filled his pamphlets with funny predictions, the highlight of which just so happened to be a lengthy argument with prominent almanac maker John Partridge over whether or not Partridge was dead, which Partridge stoutly denied (Franklin would later have the exact same argument with a rival almanac maker named Leeds, and didn’t give up until Leeds actually died).

Franklin never denied his blatant thievery. In fact, he openly rotated tidbits from different authors in his almanacs, never crediting anyone he “borrowed” from because he didn’t believe in copyrights. According to Franklin’s logic, the more familiar the writings sounded, the more they resonated with his audience as universal common sense wisdom. Basically, he felt including bylines would make Poor Richard’s Almanack less successful, so he decided not to include them, preferring to have his audience believe that he was conjuring magical witticisms out of thin air with the power of his wispy-haired skull.

2 Jack London Rewrote a Missionary’s Tale as The Call of the Wild

Naturalist author Jack London’s The Call of The Wild is one of the most famous American novels ever written. His harrowing story of a sled dog’s survival in the Gold Rush-era Yukon inspired decades of film adaptations that have helped middle school students across the globe turn their book reports in on time without ever having to actually read anything.

“I found this story to be full of striking imagery, such as Charlton Heston’s jaw.”

Considering the fact that London based most of his stories The Call of the Wild included on the time he spent catching scurvy in the punishing Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush, there’s no way he could’ve ripped anyone off, right? That would be like Carl Sagan ripping off someone else’s astrophysics background to write Contact.

The Work He “Borrowed” From:

Very few people were capable of delivering the punch-to-the-gut prose of London. As it turns out, one of those people was future Nobel Laureate Sinclair Lewis, whom London hired to supply him with plot ideas. That’s right — London hired a guy to tell him what to write about.

And to just walk around the house, looking fancy.

However, slipping a Nobel-level talent a little cash for plot-related advice was just one of the semi-nefarious ways London avoided ever having to think too hard. Other, far more ruinous allegations state that he merely stole missionary/writer Egerton R. Young’s non-fiction book, My Dogs in the Northland and rewrote it as The Call of the Wild. Apparently, London caught wind of a review of My Dogs in the Northland that specifically stated Young’s descriptions of dogs in the frozen north were far superior to his own, and sat down at his typewriter almost immediately to begin revenge-stealing Young’s work.

London straight-up admitted that much of his book was based on Young’s work, but denied that the term “plagiarism” applied because Young’s work was nonfiction, and you can’t plagiarize nonfiction. After all, writing a book based on other people’s research isn’t plagiarism, so how could London rewriting a rival’s nonfiction account of the Yukon into a best-selling piece of fiction be considered plagiarism?

“Really, if anything, Young was plagiarizing life.”

This may not seem like the soundest logic, but the area was gray enough that London managed to dodge most criticism. He even took the time to graciously thank Young for the inspiration My Dogs in the Northland had provided, which is sort of like Vanilla Ice sending David Bowie a thank-you note for “Under Pressure.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, London went on to spend a significant portion of his career defending his various works from accusations of plagiarism.

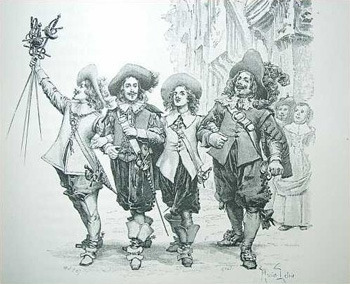

1 Alexandre Dumas Stole the Characters of The Three Musketeers

Even if you’ve never read The Three Musketeers, you’ve probably seen one of the many movies made about them. Charlie Sheen is in at least one of them.

For their creator, French author Alexandre Dumas, the Three Musketeers were a career-cementing invention. Already a prolific and respected writer, Dumas won the Harry Potter lottery when he came up with Athos, Porthos, Aramis and d’Artagnan in 1844.

Aramis was totally the Hermione of the group.

Well, we say “came up” …

The Work He “Borrowed” From:

Every major character from The Three Musketeers was lifted from the first volume of a little book called The Memoirs of Monsieur d’Artagnan. The author, Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras, outlines the primary character d’Artagnan, his Musketeer allies, the femme fatale Milady de Winter, the villainous Cardinal, and certain key plot points that would all later be duplicated exactly in The Three Musketeers. Dumas liked the characters and plot twists Sandras had created enough to claim them as his own, and started expanding upon them. From this starting point, he crafted The Three Musketeers with his primary collaborator Auguste Maquet who, incidentally, later had to sue for royalties. Dumas apparently just stole from everyone he came into contact with, like some sort of literary Hamburglar.

This wasn’t an isolated incident, either. Although a talented writer, Dumas was also a habitual and shameless glory hog. His early work was greatly aided by collaborators, assistants and “sources of inspiration,” while his later writing was characterized by a liberal use of ghostwriters. Dumas wanted to be a brand, a powerhouse of literature that could turn every project into a slam dunk. As such, he was constantly on the prowl for new story ideas, and wasn’t too concerned about looking for them in questionable places. He was basically the Thomas Edison of literature.

Today, he’d work for the Daily Mail.

It’s unclear why Dumas chose to dedicate his life to such high-level dickery, though with an estimated 40 mistresses and a shitload of personal wealth, we can probably guess that it’s because he was, at heart, a major asshole. By his own admission, Dumas was actually proud of appropriating others’ stories, because he was improving them. Pressed for a comment on the whole plagiarism thing, Dumas offered his own uniquely douchey justification for plagiarism:

“The man of genius does not steal, he conquers. He incorporates into his empire the province he annexes: he imposes on it his laws, peoples it with his subjects, extends over it his golden scepter …”

Basically, his argument was that plagiarism was like colonialization, which was his divine right as a superior mind. Since the dude’s paternal grandmother was a slave impregnated by her owner, we’re guessing this made for some pretty interesting family dinners.

https://www.cracked.com/article_21898_5-famous-authors-who-stole-their-biggest-ideas.html

Good Writers Borrow; Great Writers Steal (Politely)

Writers are thieves. Intentionally or unintentionally, we steal from other artists all the time. You might have heard this paraphrase of T. S. Eliot’s words: “Good writers borrow; great writers steal.”

5 Ways to Steal (Politely) From Other Writers

We can’t help but be inspired and influenced by the stories we consume. However, we can steal productively by borrowing from other works in a conscious manner. Here are five ways.

1. Ask yourself, “what if?”

This is one of the easiest ways to twist a well-known tale. What if Cinderella didn’t have her fairy godmother? What if Romeo and Juliet had gotten a happily ever after?

One little kink in the original plot and you have yourself a whole new story to explore.

“

Transform an old story into something new by asking, “What if?”

2. Set it in a different time and/or place.

Taking a classic story and setting it in modern times is a common trope, as seen in many versions of Shakespeare’s works. You can also put a modern tale in the past, or in space, or under the sea. Mess around with different ideas until something sparks your interest.

3. Change the genders of the characters.

One of my NaNoWriMo projects was a Sherlock Holmes retelling, except Sherlock and Watson were young women. That, along with various other twists on the characters, was enough to make familiar people fresh and intriguing.

You could do this with every character in the story, or just a few, or maybe only one person. See how the dynamics change.

4. Change the ages.

What happens if the adults in a particular situation were teenagers instead? How about the opposite? What if the teenagers became elderly people? It’s another deceptively simple tactic that can put a whole new spin on things.

5. Borrow from song lyrics.

Often times a three or four-minute song tells an incredibly complex story. If you dissect the lyrics and expand on the plot, add more characters, and bring out the heart of the song, you could have an entire short story or novel waiting to be written.

I’ve done this countless times, and I’m always pleased with the outcome.

“

Good writers borrow; great writers steal.

Don’t Forget to Make Your Story Your Own

The caveat to all of this is you can’t take one of these strategies and expect your story to be perfect. You still have to make it unique, otherwise you run the risk of plagiarism or lazy writing.

All of these tips will get you in the right direction, and from there on out, let your imagination run wild. How can you turn that “stolen” art into something new and exciting?

PRACTICE

Take one of your favorite stories (a fairytale, a Shakespearean play, a classic novel, etc.) or a favorite song and use one of the strategies above to give it a new twist. Write for fifteen minutes. When you’re finished, share the result in the comments, if you’d like. Don’t forget to give your fellow writers some feedback, too. Have fun!

https://thewritepractice.com/great-writers-steal/

Should You Be Afraid That Someone Will Steal Your Ideas? No, and Here’s Why

Can you steal ideas from other stories? What if someone steals your ideas? In fact, are your ideas even good enough at all? If you’ve ever asked questions like these, I have good news for you.

A common refrain I hear from writers is that they have an idea, but it’s too much like ___________ (fill in the blank with whatever book, movie, show you like). Or writers hoard ideas like a dragon sitting on gold, convinced that someone is about to steal them. Both of these beliefs hurt you as a writer because they are grounded in fear.

What if someone steals my idea?

Sometimes writers guard their ideas like they are top-secret, waiting for the right moment to write them. They hoard their ideas to keep others from “stealing” them. Can an idea be stolen? Yes and no.

I stumbled onto a Reddit thread recently that compared stories or films with similar plotlines that had been executed into wildly different stories.

Plot: “Tom Hanks’ flight doesn’t go well.”

Stories: Apollo 13, Cast Away, Terminal, and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. (Source: Reddit, golfandpie)

Plot: “Overprotective, single father falls into dangerous situations in search of abducted child.”

Stories: Finding Nemo and Taken. (Source: Reddit, AndySocks)

And my favorite:

Plot: “Stole a loaf of bread, went to jail, was given riches by someone, gained political office, took part in rebellion against the government, has longstanding feud with one specific government official, ultimately influences this enemy to defeat himself.”

Stories: Aladdin and Les Miserables. (Source: Reddit, zninjazero)

Were these premises stolen? *gasp!* The idea is laughable. No one walked into the writing room on Taken and said, “You know, let’s write Finding Nemo as an action film!”

But even if they had, they created something so vastly different, for an entirely new audience. All of these plotlines could be spun into unique stories, depending on the characters, setting, and voice.

Some even argue that there are only a handful of plots. (See Foster-Harris’s three basic plot patterns, Vonnegut’s story shapes, Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots or the twenty master plots of Ronald Tobias.) The originality isn’t in the core plotline — it’s in the unique, specific execution of that plot, of that character’s journey.

The point is this: an idea can’t be stolen. A finished book can be stolen in whole or parts — that’s called plagiarism or theft (see the copy and paste scandals happening right now). But an idea, one you’re just talking about? One that isn’t developed or finished? That can’t be stolen.

“

An idea can’t be stolen. Two writers who begin with the same idea will create two vastly different stories.

I’m just asking if it’s good

Once a writer gets beyond the hoarding phase and begins sharing ideas, too often they only do it to secure approval. My students sometimes come in or email me, “I have this idea. Can you tell me if it’s good?” Some writers do this same thing, sending ideas and half finished chapters to authors they love for feedback (stop doing this, please).

My answer: Who knows? Who knows until you execute it fully?

In my early days of teaching, I probably would have guided writers to ideas I found more “worthy,” but I have since realized that I am not the gatekeeper of good ideas. This frustrates students to no end.

“Just tell me if it’s good!” they say, exasperated.

I tell them, “Look, if you had come to me ten years ago and said you want to write a story about tornadoes and sharks, I would have told you to pick either sharks or tornadoes. Now there are six (YES, SIX!) Sharknado movies. Execution is everything. Until you write it and try it out, who knows if it will find an audience?”

Elizabeth Acevedo, author of The Poet X, has talked candidly about her frustration with a professor in her MFA program who had assigned a poem about nature. She’s from New York City, and she’d chosen to write about rats.

Her professor told her rats weren’t noble. That they weren’t a good idea. Then she wrote an astonishing poem that captured her unique point of view and voice. She would go on to publish a best-selling book and electrify audiences with her poetry and prose.

Stop waiting for someone to tell you an idea is “good.” If it is something you’ve been mulling over for a while, something you can’t get out of your head, write it down and finish it. Only then can you evaluate where it lacks originality and then you can revise.

The same, but different

There are entire books about how real artists build and adapt from ideas already in the world (see Austin Kleon’s book Steal Like an Artist, or the entire Shakespeare canon). When you find ideas in others’ work that capture your attention and keep you up at night? Spin those in your own direction, in your own voice.

You may start in the same place as another writer, but you will likely end up somewhere different because you have a unique point of view.

Genre fiction works on the entire principle of “the same, but different.” Anyone who picks up a romance expects two people to meet, experience setbacks and complications, and then finally accept they are in love. The romances that rise to the top tend to execute those expectations in an unexpected or fresh way.

So stop worrying about similarities when you know you’re not copying and pasting someone’s work. I would argue most developing writers mimic their favorite authors at first anyway, and it is a natural part of growth. Try out different voices and discard those that you outgrow. It will help you find your own voice.

It’s unproductive to remain paralyzed in fear that your idea will be stolen or that it’s too similar to something else. Stop letting those excuses keep your from writing your story.

What ideas have you been hoarding or worrying were too much like something else to try?

PRACTICE

It’s your turn to “steal” an idea. Using one of the movie plots above, spin a new version by adding character, setting, or voice to create a unique premise.

Or do you have an idea you’ve been saving up, one you’ve been too afraid to try? Start now. Write the first paragraph or page.

Take fifteen minutes to write. When you’re done, share your writing in the comments, and be sure to leave feedback for your fellow writers!